Birthday: January 29, 1920

Birthplace: Muscoda, Wisconsin

Family: Eberhardt &Amelia Faust

Occupation: The Hub (men clothing store) and Wisconsin Bell

Branch: Army and then Air Corp

Unit: Radar

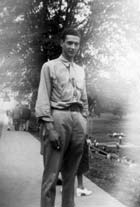

E. Jeff Faust

E. Jeff Faust

E. Jeff Faust

E. Jeff Faust

E. Jeff Faust

E. Jeff Faust

E. Jeff Faust

E. Jeff Faust

E. Jeff Faust

E. Jeff Faust

E. Jeff Faust

E. Jeff Faust

E. Jeff Faust

Everett Faust, also known as Jeff, fought in World War II. He was a brave and courageous soldier. He died peacefully at his home on January 26, 2000. Here is his story, passed on by his wife.

Jeff Faust was drafted when he was 21 years old on May 29, 1941. Soon after, he began what he thought would be one year's service. This is an account of his experiences in the army to his discharge in September 1945. Faust preferred not to go into great detail about actual combat. However, he did share some of his interesting army experiences with his family. When he was discharged, he was a Tech Sergeant in the 93rd Coast Artillery.

When he was drafted, Faust had a fairly good job with a Madison printing company. His employer thought he could arrange a six-month delay to train a replacement, but Faust declined, wishing to get his year over as soon as possible. At the time, it seemed to him that the chances of America becoming involved in the European war were remote. He conceded that if he hadn't been drafted, it was likely he would have enlisted once war was declared.

Faust was inducted at Camp Grantin, Illinois along with a group of men from Wisconsin, Michigan, and Illinois. Shortly thereafter, they were sent to basic training at Camp Davis, North Carolina, about 30 miles from Wilmington.

Basic was the right word for it. His first sergeant was illiterate. When it became necessary to call role, he had to ask a recruit to do it for him. The sergeant could not even write his own name. Faust remembers the camp to be slightly disorganized, with a small number of regular army non-comm.'s. referred to as "the cadre" doing much of the day-to-day operating chores of running the camp.

His unit was then called the 95th Coast Artillery. His job would eventually involve working with radar and communications, something he had no background in. In the meantime, the work his unit was engaged in would be something far different.

Camp Davis was just being built. Many of the buildings were up, but his unit found itself grubbing stumps, digging ditches and building roads. They also landscaped the parade grounds and thereafter spent many hours breaking it in.

The Camp consisted of approximately 20,000 men, half black and half white. They were housed in segregated quarters. Virtually all the recruits were Northerners in this Southern setting. The Blacks, unaccustomed to Jim Crow style treatment accorded them by Southern civilians frequently erupted in fighting and rioting, sometimes growing to include hundreds. Faust remembers several of the grievances, which would touch off disturbances. Bus drivers would kick blacks off and give their seats to whites or make blacks sit in the back of the bus. They were not allowed full participation in U.S.O. activities. State liquor stores would refuse to sell to them and some restaurants to serve them. Along with insulting name calling, it is apparent that there was some justification in the dissatisfaction. By and large, the disturbances were usually confined to fist fights and brawling.

Faust expected to be furloughed for Christmas and New Year's, but the events at Pearl Harbor on December 7th, changed everything. His furlough was canceled and he would not see home again for three years. Like it or not, he was in for the duration. On December 8th the men at Camp Davis began packing up the communications and radar gear. By December 18th, the entire camp of 20,000 men was on their way to a camp in the Mojave Desert, near Barstow, California.

Once there, they camped in tents. The full impact of how serious army living would be had not yet struck home for the young draftee. At Camp Davis, he had briefly been made a Corporal but was busted for mincing his Sergeant's Boston accent in front of some troops on a hike. He didn't care; readily admitting the incident to the officer the matter was brought to. While guarding the camps' water supply in the Mojave Desert one night, he got a further reprimand. Out of boredom on this particular night, Faust set up a spotlight, and as a series of rabbits hopped across the light, he put in a little unauthorized target practice. The site was located a short distance from the main camp, on a hill. After he had shot 5 or 6 rabbits, he discovered several trucks, attracted by the gunfire, making their way up the hill with reinforcements.

Soon army life would take a more serious turn. In mid-January of 1942, the men were transported by truck to Oakland and shipped out to Hawaii. The crossing took 21 days as the ships zigzagged to avoid enemy submarines. Still, the destroyers escorting the convoy sunk two Japanese submarines during the crossing. The 95th Coast Artillery became the 93rd and was assigned to General MacArthur as a detached service battalion. The convoy put in at Honolulu Harbor because Pearl Harbor was still blocked by sunken ships.

The only uniforms the men had were olive drab, heavy woolen ones, and Faust remembers them as miserably unsuitable apparel for the tropics.

Once in Hawaii, their job was to install radar devices on the Japanese facing side of the mountains. This was to make it unlikely that the Japanese would be able to attack with low flying aircraft as they did at Pearl Harbor. One night Faust and a buddy were guarding a radar installation during a 72-hour stretch of duty when the buddy made the mistake of putting a cigarette in his mouth and lighting it in the open. He was promptly shot in the shoulder for the folly of exposing his where abouts to a sniper. It was the first time Faust witnessed a man being shot and he was never able to light a cigarette outside at night without the memory of this incident making him alert and uneasy for a moment. Snipers were commonplace in Hawaii in these early days of the war and Faust remembers having to be constantly on the alert when working in the mountains.

Another night while again on guard duty, Faust heard footsteps and called out, "Halt!" Getting no response, he repeated the order. Again the intruder advanced with out a response, so Faust fired, dropping the unanswering visitor dead in his tracks. Faust had shot and killed his first and only dairy cow of the war.

After a period of months in Hawaii, Faust was sent with his unit on the invasions of Johnson and Christmas Islands, which were located in the South Pacific. Their jobs, as it would be in the ensuing island hopping was to set up communications and radar as soon as ground was taken. Faust remembers the Japanese opposition as light on these first two islands, the enemy being greatly outnumbered.

Following Rest & Rehabilitation (R&R) in Hawaii, Faust's unit was next sent on the invasion of the Gilbert Islands, also located in the South Pacific. The marines fought on Tarawa with heavy losses. The U.S. won Tarawa in 3 days of bloody fighting. Of the 3,000 enemy troops and 1,800 civilian laborers on the island, the marines captured only 147 Japanese and Koreans alive. The United States suffered 3,110 casualties in one of the war's most savage battles. Faust went in with the army on Makin and although the enemy opposition was not as intense, many troops still lost their lives due to a miscalculation. The troops were heavily laden with full field pack, ammunition, rifle, shovel, and steel helmets as they disembarked from landing craft in what was supposed to be 3 to 4 feet of water. Apparently, the tide was not taken into consideration because the troops found themselves floundering in 14 feet of water and many drowned. Faust managed to free himself of everything but his rifle and 8 rounds when he finally made the beach.

His next major stint was for 9 months on Abemane Island setting up communications that reached as far as New Zealand and Tahiti. The island was very narrow and 11 miles long. As they had on other islands, they built air raid shelters. Here they used 55-gallon gasoline drums filled with sand. A supply ship would stop about once a month with food, 3.2 beer, mail and supplies. Supplies for replacing electronic parts were hard to come by, so often it was necessary to improvise with whatever was available. Another problem was moisture affecting the parts.

In their spare time, Faust and his friends got an old Japanese landing barge running, painted it red, white, and blue, and used it as a fishing trawler. Finally in 1943, they were relieved and sent back to Hawaii for R&R.

Faust said they spent the first week resting and getting decent food and then went out to enjoy wine, women, and song. He said you lived it up on R&R because you might not have another chance. Faust said that the real rowdies in Hawaii were not those troops back from action who appreciated what R&R meant, but those who hadn't got any further than Hawaii.

His unit was soon sent back to the action in the Marshall Islands, having been classified as "experienced under fire". From there, they went to the Marianas. By this time Faust had "gone native", having contracted malaria and dengue fever.

Malaria was common and Faust said they just gave you quinine and you kept going. Dengue fever was a disease he remembers with no fondness. He described it as going from extremely high temperature to abnormally low temperature and back and forth. Although it only lasted a couple weeks, it left him weak for a considerably longer time. As if that wasn't enough, Faust and a small number of others in his unit also contracted elephantitus.

In June of 1944 he was on a ship following the invasion of Saipan when he was shocked with a sight best forgotten, but unforgettable. The water was discolored with blood and contained arms, legs and bodies floating lifeless, victims of the battle for the beach.

Faust didn't get past the beachhead hospital on Saipan because of Elephantitus and in July was transported from this tent hospital to one in Hawaii, converted from a schoolhouse. The hospital in Hawaii was so crowded that they had beds in the hallways. He was next flown to a V.A. hospital in Iowa, seeing Women's Army Corps (WAC) for the first time, on the fight.

After a year in hospitals, Faust was released and assigned to the air corps in Shepardfield, Texas, briefly in 1945. From there he came full circle and was a radio mechanics instructor at Truax Field in Madison until his discharge in September of 1945.

His view of death while in the war zone was "The first few times you witness the destruction of human beings, it really shakes you up. After a while you find yourself saying `Gee, I'm sorry, but it could have been me,' pass it off, and go on. There's nothing you can do about it."

The time he spent in hospitals, where he was around other people, probably made the adjustment back to civilian life much easier. Living in the war theater makes a person's attitude toward other people change. Faust describes it as a kind of "don't give a damn attitude" towards being aware of or considerate of people who had not shared the same experience. This was not something intentional, but gradually developed and took time to overcome.

He was a patriotic man who loved his country. He was glad to do his duty and thankful he survived, but he would never do it again. "It was a waste of four and a half years of my life."

He has a picture of his company of 250 men before they started island hopping. In 1945, only seven including him were alive!

under Learn and Serve American Grant #00LSFWI104